The enduring tale of Oz has captivated generations, but beneath the surface of glittering emeralds and yellow brick roads lie fascinating discrepancies, or "wheelers," between L. Frank Baum's 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the iconic 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. This isn't just a simple adaptation; it's a creative reimagining where core narrative "wheels" spin in entirely different directions, offering distinct experiences of Dorothy's journey. Understanding these "Wheelers in Oz Literature: Book vs. Movie Comparison" allows us to appreciate the genius of both works and the art of adaptation itself.

At a Glance: Key Differences Driving the Oz Narratives

- Slippers: Book's magical silver; Film's iconic ruby (for Technicolor).

- Kansas Echoes: Film invents Kansas alter-egos (Miss Gulch/Witch, Marvel/Oz, farmhands/companions); Book has none.

- Tin Man's Past: Book details his tragic origin by the Wicked Witch of the East; Film leaves it unexplained.

- Emerald City's Hue: Book's citizens wear green glasses to make everything appear green; Film's city is actually green.

- Oz's Appearances: Book's Oz appears differently to each friend over days; Film's Oz is a luminous head to all at once.

- Wicked Witch: Book's Witch is a cyclops and not initially after the slippers; Film's Witch has a crystal ball and covets the slippers from the start.

- Journey's End: Book's Dorothy is conscious and loses slippers on landing; Film's Dorothy has a head knock, making Oz a dream.

The Shifting Sands of Silver and Ruby: Dorothy's Magical Footwear

Perhaps the most visually striking "wheeler" between the book and the movie is Dorothy's slippers. In L. Frank Baum's original novel, they are a dazzling silver. These aren't just any shoes; they are imbued with powerful magic, crucial for Dorothy's eventual return home. Their understated elegance fits the ethereal magic of the book.

However, the 1939 film adaptation, a groundbreaking achievement in its time, famously changed these to ruby slippers. Why the switch? The answer lies in the nascent technology of Technicolor. Filmmakers wanted to maximize the visual impact of the new color process, and the vibrant red of ruby slippers would pop spectacularly against the yellow brick road and the green hues of Oz. This decision wasn't just aesthetic; it fundamentally altered an iconic visual element, forever linking the ruby slippers to the popular imagination of Oz. This change, driven by cinematic innovation, became a narrative "wheeler" that audiences instinctively recognize.

Beyond the Rainbow: Kansas Echoes in Oz

One of the most profound and emotionally resonant "wheelers" is the film's ingenious framing device involving Dorothy's Kansas life. The movie introduces characters like the stern Miss Gulch, the mysterious Professor Marvel, and the well-meaning farmhands Hunk, Hickory, and Zeke. Later, these characters reappear in Oz as the Wicked Witch of the West, the Wizard, the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion, respectively.

This elaborate system of Kansas alter-egos is an invention of the movie and is completely absent from Baum's novel. In the book, the Oz characters are unique, existing in their own right, with no connection to Dorothy's life back on the farm. The film's choice to link them creates a powerful psychological dimension: is Oz real, or a vivid dream born from Dorothy's everyday anxieties and desires? It anchors the fantastical journey to Dorothy's inner world, giving the narrative an emotional resonance that the book, focused purely on adventure, doesn't explore in the same way. This narrative "wheeler" fundamentally reshapes the story's interpretation.

The Tin Man's Heartache: A Deeper Origin Story Lost

The Tin Man, perpetually seeking a heart, is a beloved character in both versions, but his tragic backstory differs significantly. In Baum's novel, the Tin Woodman's origin is detailed with a dark, almost gothic twist. He was originally a human woodman, deeply in love, until the Wicked Witch of the East grew jealous. She bewitched his axe, causing it to repeatedly chop off his body parts, one by one. Each lost part was replaced by a tinsmith, until he was entirely made of tin, ultimately losing his human heart (and his ability to love). This explanation provides a poignant layer to his quest.

The 1939 film, however, does not detail the Tin Man's origin story. His desire for a heart is presented as an inherent characteristic, a simple starting point for his quest. This streamlining simplifies the narrative, keeping the focus on the immediate adventure rather than delving into extensive backstories. It's a "wheeler" that trades complexity for narrative efficiency, suitable for the film's musical, family-friendly tone.

Emerald City's True Colors: Green Glasses vs. Green Everything

The dazzling Emerald City is a hallmark of Oz, but its verdant appearance is perceived differently. In the novel, Baum describes the Emerald City as truly magnificent and bejeweled, but not entirely green in its natural state. Instead, its inhabitants (and visitors) are required to wear green-tinted spectacles, ensuring that everything appears green. This clever conceit highlights the power of perception and the wizard's control over the city's mystique. Interestingly, the book also notes that there are no animals in the Emerald City, adding to its artificial, almost pristine feel.

The film, leveraging Technicolor, takes a more direct approach. The Emerald City is visually depicted as entirely green, from its towering spires to its bustling streets. There's no need for special glasses; the city itself is the vibrant hue. This change offers immediate visual gratification, making the city an unambiguous spectacle of color. It's a "wheeler" that prioritizes visual splendor over a more subtle narrative trick, creating an unforgettable cinematic landscape.

Oz's Many Faces: A Personal Encounter vs. a Group Audience

The titular Wizard of Oz is a figure of immense power and mystery, but his initial interactions with Dorothy and her friends diverge. In the novel, Oz is far more elusive and manipulative. He appears to each of the four friends separately, over four consecutive days, and takes on a different, often fearsome, form for each visitor:

- To Dorothy, he is a colossal, luminous head.

- To the Scarecrow, he appears as a beautiful woman.

- To the Tin Man, he manifests as a fearsome beast.

- To the Cowardly Lion, he is a ball of fire.

This theatricality underscores Oz's cleverness and his ability to project different personas to intimidate or impress.

The film simplifies this dramatically. Dorothy and her friends visit Oz together, and he appears to them collectively as a single, luminous head. This streamlines the narrative, maintaining a consistent visual for the Wizard's initial intimidating form and keeping the group together for exposition. This "wheeler" shifts the focus from Oz's individual deception to the collective awe (and eventual disappointment) of the companions.

The Wicked Witch of the West: Cyclops, Crystal Ball, and Slippery Motives

The Wicked Witch of the West is perhaps the most iconic villain in cinematic history, largely thanks to Margaret Hamilton's portrayal. Yet, her character, appearance, and initial motivations undergo significant "wheelers" from page to screen.

In Baum's book, the Wicked Witch is described with a more monstrous appearance, notably as a cyclops with a single, all-seeing eye. Filmmakers wisely opted for a more conventionally menacing, green-skinned villain with a crystal ball as her surveillance tool, making her character both terrifying and visually captivating for the big screen.

Crucially, in the novel, the Witch is not initially after Dorothy's silver slippers. She only becomes interested in them after capturing Dorothy and the Cowardly Lion. Her initial focus is on exercising her dominion and enslaving Dorothy. The film, however, establishes her relentless pursuit of the ruby slippers from the moment she appears, making them the central MacGuffin and elevating their importance in the plot. This narrative "wheeler" immediately sets up a clear conflict and objective for the villain, driving much of the film's tension.

Glinda's Protective Kiss: A Mark of Magic Downplayed

Another subtle but significant detail that serves as a protective "wheeler" in the book is Glinda's kiss. In the novel, Glinda's kiss leaves a visible, protective mark on Dorothy's forehead. This mark serves several purposes: it helps Dorothy see the true form of Oz later on, and it also protects her from the Flying Monkeys, who are unable to harm anyone marked by the Good Witch.

The film largely downplays this detail, omitting the visible mark and its explicit protective qualities. While Glinda's magical presence is felt, the tangible, protective token is removed, simplifying the magical mechanics and focusing more on Glinda's guidance rather than a specific charm.

Perils and Rescues: Poppies, Kalidahs, and Winged Monkey Tactics

The journey through Oz is fraught with danger, and the specifics of these perils and their resolutions also undergo "wheelers."

- The Poppy Field Rescue: In the book, the Wicked Witch of the West has no involvement with the deadly poppy field. Instead, the resourceful Scarecrow and Tin Woodman carry Dorothy and Toto out of the field, as they are not affected by the poppies' sleep-inducing scent. The Cowardly Lion is saved through a clever chain of events: the Tin Woodman rescues the Queen of the Field Mice from a wildcat, and in gratitude, she and her myriad mice pull the Lion out on a cart. The movie depicts a simpler, magical intervention: Glinda conjures a magical snowfall to awaken them. This cinematic solution is more direct and visually dramatic.

- Forest Threats: Baum's novel includes fearsome creatures called Kalidahs, beastly monsters with the body of a bear and the head of a tiger, as a real threat in the forest. The movie simplifies this lurking fear into the iconic and memorable phrase, "Lions, and tigers, and bears, oh my!" This cinematic "wheeler" transforms a specific monstrous threat into a general, child-friendly expression of fear.

- Witch's Capture Tactics: When the Wicked Witch of the West captures Dorothy and the Lion in the book, the Winged Monkeys are far more destructive. They dismantle the Scarecrow and beat the Tin Woodman severely, highlighting the Witch's cruelty and leaving the friends in dire straits. In the movie, the Witch's capture is less violent towards the companions; she primarily takes Dorothy, allowing her friends to remain intact and enabling them to plan a daring rescue, making for a more active and heroic subplot.

A Dream or a Reality? Dorothy's Journey Home

Perhaps the most significant "wheeler" dictating the entire tone and interpretation of Dorothy's adventure is the nature of her journey to Oz and her return.

The film portrays Dorothy fainting from a head knock during the tornado, which then frames her entire Oz experience as a vivid, fantastical dream. Her journey home involves clicking her ruby slippers and wishing to be back in Kansas, only to wake up surrounded by her family, who assure her it was "only a dream." This interpretation offers a comforting closure, a classic narrative device that grounds the fantasy in reality.

In the book, however, Dorothy's experience is unequivocally real. She simply dozes off as the house is carried away by the tornado but remains fully conscious for her return journey. Moreover, her silver slippers, the means of her return, are lost in the desert upon landing back in Kansas. This detail underscores the reality of her adventure and the tangible consequences of her journey, rather than dismissing it as a mere figment of imagination. This fundamental "wheeler" profoundly impacts how readers and viewers engage with the truth of Oz.

The Craft Behind the Changes: Why Adaptations Spin New "Wheelers"

Understanding these "wheelers" isn't about declaring one version superior; it's about appreciating the unique challenges and opportunities of adaptation. The 1939 film, The Wizard of Oz, was a cinematic marvel of its time.

- Title: The Wizard of Oz

- Genre: Musical, Fantasy

- Length: Approximately 102 minutes

- Director: Victor Fleming

- Writers: Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf

- Main Cast: Judy Garland (Dorothy), Ray Bolger (Scarecrow/Hunk), Jack Haley (Tin Woodman/Hickory), Bert Lahr (Cowardly Lion/Zeke), Billie Burke (Glinda), Frank Morgan (Oz/Fortune Teller), Margaret Hamilton (Wicked Witch of the West/Miss Gulch).

- Cinematography: Harold Rosson, Arnold Gillespie (noted for Kansas in black and white, Oz in color).

- Music: Herbert Stothart (won Oscar for Best Original Score), "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" (won Oscar for Best Original Song).

- Trivia: The "oil" used for the Tin Man was famously chocolate syrup.

Filmmakers made choices driven by:

- Technological Innovation: The ruby slippers are the clearest example, capitalizing on Technicolor's vivid palette.

- Narrative Streamlining: Condensing subplots (Tin Man's origin), simplifying character interactions (Oz's appearances), and focusing the villain's motivations made the story more accessible for a two-hour musical.

- Thematic Interpretation: The dream framing device added a layer of psychological depth and emotional safety for audiences, making the fantastical more palatable.

- Target Audience: The film aimed for broad family appeal, leading to some softening of the book's darker elements (e.g., the Witch's cyclopean eye, the violence of the Winged Monkeys).

L. Frank Baum's novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), on the other hand, was the first of a 14-book series. It established a sprawling, magical world, intended to transport readers entirely to a land of fantasy. Baum wasn't bound by cinematic runtime or color palettes, allowing for greater detail, more complex backstories, and a more literal approach to magic. His aim was to create a truly American fairytale, free from the grim undertones of European folklore.

Navigating the Different Paths: Which "Wheeler" is Right for You?

Understanding these myriad differences — these narrative "wheelers" — doesn't diminish either work. Instead, it enriches our appreciation for both. The 1939 film is a masterclass in cinematic adaptation, a classic that captured the hearts of millions and defined Oz for generations. It distilled Baum's expansive world into a potent, emotional, and visually stunning musical.

The novel, meanwhile, offers a richer, often more whimsical, and sometimes darker tapestry of Oz. It presents a more complex world with subtle magical mechanics and a protagonist whose journey is undeniably real. For those who delve into the book, it often feels like discovering a hidden continent within a familiar world, revealing new layers of depth and wonder.

There's no single "right" version. Each serves a different purpose and offers a unique experience. If you've only ever watched the film, reading Baum's original work can be a revelation, expanding your understanding of this beloved universe and its intricate lore. Conversely, if you're a long-time reader, watching the film with an eye for its creative "wheelers" offers new insights into how stories are reimagined for different mediums.

Beyond the Yellow Brick Road: The Legacy of Oz's Narrative "Wheelers"

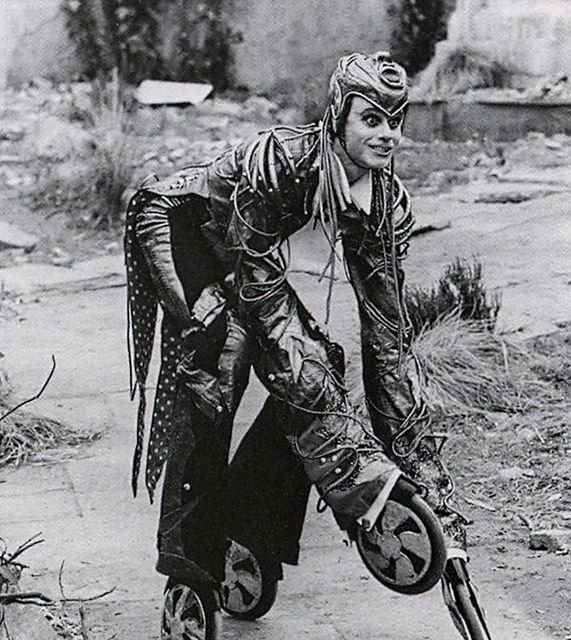

The creative decisions made in adapting The Wonderful Wizard of Oz set precedents for countless adaptations that followed. They demonstrate how source material can be honored while being transformed to suit a new medium, audience, and artistic vision. These foundational "wheelers" continued to influence subsequent adaptations and reinterpretations of Oz, proving that a truly great story can be told and retold, each time offering new perspectives. To dive deeper into how these narrative mechanisms continue to evolve in other Oz stories, you might want to Explore the Return to Oz Wheelers.

So, whether you prefer your slippers ruby or silver, your Oz a dream or a destination, the journey itself—and the fascinating "wheelers" that drive its many forms—remains one of literature and cinema's most enduring magical feats. Why not take a stroll down both yellow brick roads and discover which narrative "wheelers" resonate most with you?